한국 대학생과 미국 대학생의 AAC 사회어 그림 상징 인식에 대한 문화적 차이

Cultural Differences on the Recognition of Social Word AAC Graphic Symbols between Korean and American Undergraduate Students

Article information

Abstract

배경 및 목적

AAC 상징 인식에서 도상성은 필수적이다. 다수의 사람들이 핵심 단어로 사용하고 있는 사회어의 성격과 AAC 상징의 특성을 고려하여, 본 연구에서는 한국인과 미국인 대학생을 대상으로 AAC 사회어 그림 상징 인식에 도상성과 문화적 배경이 미치는 영향을 살펴보고자 하였다.

방법

48명의 대학생이 참여하였으며, 10개의 사회어를 나타내는 그림 상징들은 Picture Communication Symbols와 이화-AAC 상징에서 각각 10개씩 선정하였다. 참가자들에게 투명성 과제(transparency task)와 반투명성 과제(translucency task)를 실시하였다.

결과

투명성 과제와 반투명성 과제 모두에서 집단과 상징 유형에 대한 이원상호작용이 통계적으로 유의하였다. 또한 투명성 과제에서 정반응 수의 합과 반투명성 과제에서 평정 점수의 합에 따른 개별 상징의 서열에 대한 상관관계가 전체 참가자 모두에서 통계적으로 유의한 정적 상관을 보였다.

논의 및 결론

본 연구는 동일한 단어를 표현하는 AAC 상징이라 하더라도 단어, 상징, 문화적 특성이 AAC 사회어 그림 상징 인식에 영향을 미칠 수 있음을 확인한 것에 의의가 있다. 또한, 두 종류의 도상성 수행 결과에 따른 개별 상징 서열에 대한 정적 상관관계는 그림 상징의 투명성과 반투명성이 AAC 상징 인식에 영향을 미칠 수 있음을 시사한다. 따라서 AAC 상징 선정 시 그림 상징의 투명성과 반투명성 정도에 대한 고려의 필요성을 시사한다.

Trans Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this study is to examine the effects of iconicity and cultural background on the recognition of social word AAC (augmentative and alternative communication) graphic symbols between two cultural groups.

Methods

The participants of the study were 48 undergraduate students (24 Koreans and 24 Americans), and 20 graphic symbols of 10 social words were selected for the stimuli from PCS and Ewha-AAC symbols developed in Korea. The transparency task asked the participants to guess and write down the meanings in 30 seconds for each symbol. For the translucency task, the participants marked their degree of agreement with the meaning of the symbol on the 5-point rating scale, given 20 seconds for each slide.

Results

First, the Korean students guessed the meanings of social word AAC symbols more correctly than the American students in Ewha-AAC symbols. Second, the Korean students gave higher scores to Ewha-AAC symbols, while the American students gave higher points to PCS. Third, there were moderate and positive correlations between the performances of the iconicity tasks.

Conclusion

The results suggest that cultural background of words, symbols can be influencing factors for the recognition of graphic symbols. In addition, the positive correlations between the performances of the iconicity tasks suggest that transparency and translucency of graphic symbols may affect the symbol recognition. Moreover, the results suggest the need to consider the degree of transparency and translucency of graphic symbols when selecting symbols for AAC.

For successful provision of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) service, four essential components, symbols, aids, techniques, and strategies, are necessary. Symbols correspond with words or sentences of language. Aids are physical tools for loading symbols. AAC users can choose techniques to select a message which users want to deliver, and establish strategies for an efficient way to deliver the message (Park & Kim, 2010). When classifying AAC symbols, using additional aid determines unaided symbols and aided symbols (Beukelman & Mirenda, 2012). Gestures, vocalization, and manual sign systems are typical unaided symbols, because these symbols only use one's own body without any additional aid to deliver messages. Tangible symbols, pictorial symbols, and orthographic symbols belong to aided symbols. Photographs and line-drawing symbols are pictorial symbols, and orthographic symbols include braille, finger spelling, and orthography (Beukelman & Mirenda, 2012; Kim, 2014). Aided symbols require additional tools to deliver the message, such as a communication board, voice output communication aid, and various electronic equipment. Han (1998) suggested that aided symbols are based on visual representation, and such characteristic of aided symbols enables individuals with physical disabilities to indicate symbols with assistance of additional tools. Representational symbols including photographs, orthography, and graphic symbols are widely used in AAC intervention because of permanent display and iconicity (Pecyna Rhyner, 1988). In British and American culture, various kinds of graphic symbols have been developed. Picture Communication Symbols (PCS; Mayer-Johnson) is the most widely used graphic symbol for AAC around the world. Also, there are Widgit symbols from the United States and the United Kingdom, Pictograms from Canada, and Blissymbols developed in Canada (Beukelman & Mirenda, 2012; Kim, 2014). In Korea, Park et al. (2014) developed Ewha-AAC symbol which contains 5,000 graphic symbols appropriate for Korean culture and daily life. Ewha-AAC symbol is used in communication teaching-learning materials developed by the Korea National Institute of Special Education and MY AAC software developed by the NCSoft Cultural Foundation. As a variety of graphic symbols are used around the world, the individual needs for selecting appropriate and specialized graphic symbol sets are on the rise (Choi & Han, 2015). According to Light & Binger (1998), for detail word or sentence expression via graphic symbols, both factors of AAC users and communication partners have to be considered. Park, Snell, & Allaire (2004) suggested the need to consider AAC users’ age, personality, knowledge of language and communication partners’ age, familiarity of AAC for graphic symbol selection.

The recognition of symbols, especially graphic symbols, is an important matter for AAC users and their communication partners. For recognizing graphic symbols of AAC, iconicity (Hetzroni, Quist, & Lloyd, 2002; Huang & Chen, 2011; Kozleski, 1991; Lloyd, Fuller, & Stratton, 1997; Schlosser & Sigafoos, 2002), cultural familiarity with graphic symbols (Blake Huer, 2000; Chompoobutr, Potibal, Boriboon, & Phantachat, 2013; DeKlerk, Dada, & Alant, 2014; Nigam, 2003), and language knowledge (Harris & Reichle, 2004; Hartley & Allen, 2015; Kirkham, Stewart, & Kidd, 2013; Light & Lindsay, 1991; Romski & Sevcik, 1993, 2005) are suggested as influencing factors. Among various influencing factors of symbol recognition, iconicity is a significant factor in learning graphic symbols (Basson & Alant, 2005; Hetzroni et al., 2002; Huang & Chen, 2011; Kozleski, 1991; Schlosser & Sigafoos, 2002) and selecting graphic symbol sets for AAC users (Lloyd et al., 1997). The iconicity which is including transparency and translucency, refers to the extent of similarity between a symbol and a referent (Alant, Zheng, Harty, & Lloyd, 2013). Based on the notion of iconicity, the iconicity hypothesis states that the similarity of a graphic symbol with the referent may affect learning the graphic symbol and memorizing the associations between the graphic symbol and the referent (Lloyd et al., 1997; Schlosser & Sigafoos, 2002). Many studies supporting the iconicity hypothesis (Choi & Song, 2010; Fuller & Lloyd, 1991; Mizuko, 1987; Mizuko & Reichle, 1989; Schlosser & Sigafoos, 2002; Wilkinson & Jagaroo, 2004) indicate that graphic symbols which have higher iconicity are recognized and learned more easily. High iconicity of symbols make individuals recognize and understand the referential meaning of symbols easily (Brown, 1978), but iconicity is not the only factor of symbol recognition. Other various influencing factors described above also have influences on the recognition of symbols (Bondy & Frost, 1994; Lloyd et al., 1997; Schlosser & Sigafoos, 2002).

Traditional strategies for vocabulary selection of AAC is conducting ecological inventories to investigate AAC users’ communication environments and situations, and using communication diaries to collect communication functions of AAC users, and comparing standard vocabulary list to the collected vocabulary list for the composition of individually appropriate vocabulary list (Morrow, Mirenda, Beukelman, & Yorkston, 1993). Although general knowledge of vocabulary development is a basic factor in selecting vocabulary for AAC (Park et al., 2004), each AAC user has a different degree of knowledge and necessity of vocabulary. Other factors should be considered as well. Lloyd et al. (1997) suggested that the assessment of AAC users’ literacy skill which can affect vocabulary selection depends on the levels of the skill. The authors additionally proposed intellectual ability, age, and interest as developmental factors for vocabulary selection. Furthermore, the involvement of multiple informants (Fallon, Light, & Paige, 2001) can be contained within influencing factors of vocabulary selection. Communication context and communication partners are additional factors (Park et al., 2004). In the study of Bornman & Bryen (2013), the researchers checked the social validity of specific vocabularies which are related to disclosing one's experiences as victims of crime or abuse, and Bryen (2008) collected and checked the contextual vocabularies for the adult AAC users which are categorized as college life, transportation, health management, and so on. Core vocabulary, vocabulary which is frequently and commonly used, is an important source of vocabulary selection for AAC (Beukelman, McGinnis, & Morrow, 1991; Fallon et al., 2001; Trembath, Balandin, & Togher, 2007). Core vocabulary, which include frequently occurring words or expressions and vocabulary that is usually used by various individuals (Kim, Park, & Min, 2003; Trembath et al., 2007; Vanderheiden & Kelso, 1987), enables individual who use AAC to communicate efficiently and effectively even with small numbers of it (Vanderheiden & Kelso, 1987). Moreover, core vocabulary enables AAC users to participate in balanced communication (Park, 2014; Romski & Servcik, 1988) by including diverse communication functions, expressing social friendliness and manners, and delivering information (Light, 1988). Numerous studies about core vocabulary have stated social words as early developed vocabulary or frequently used vocabulary in one's life (e.g., Banajee, Dicarlo, & Stricklin, 2003; Boenisch & Soto, 2015; Lee, Chang, Choi, & Lee, 2009; Lee, Pyun, & Kwak, 2011). Lee et al. (2009) found infants acquire social words (e.g., ‘No’, ‘Hi’) which are used in parent-child interactions faster than other words. Lee et al. (2011) stated that frequently used nouns related to family, body parts, and daily necessaries in daily activities, and social words such as ‘Hi’, ‘Bye’ are the basic learning vocabulary for children with developmental disabilities. These tendencies in core vocabulary has consistency in discordance of language (Boenisch & Soto, 2015; Robillard, Mayer-Crittenden, Minor-Corriveau, & Bé-langer, 2014; Trembath et al., 2007), and age (Banajee et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2003). For balanced communication in AAC, teaching the use of social words such as emotional expressions and simple comments for something as well as other core vocabulary is important (Park, 2014). In the study of Choi & Han (2015), many children who start to learn the use of AAC devices initially learn short phrases or sentences (e.g., ‘Hi’, ‘Thank you’). This can help initial AAC users and partners communicate effectively and correctly in real communication situation (Choi & Han, 2015), and make AAC users have more opportunities to participate in social activities.

Considering concepts of social words and factors influencing symbol recognition, social word AAC symbols with high iconicity and cultural background may affect functional communication. In this regard, the purpose of this study is to examine the effects of iconicity and cultural background on the recognition of social word AAC graphic symbols between two cultural groups. For this purpose, the transparency task and translucency task on social word AAC symbols from PCS developed in the United States, and Ewha-AAC symbol developed in Korea were conducted for the Korean and American undergraduate students. First, we aimed to compare the performance of transparency task of social word AAC symbols between two cultural groups. Our second aim was to examine differences on the performance of translucency task of social word AAC symbols between two cultural groups. Lastly, we aimed to explore how and what kinds of correlations would exist between the transparency task performance and the translucency task performance according to each social word AAC symbol.

METHODS

Participants

The participants for this study included undergraduate students who were studying communication disorders. A total of 48 female students (24 Koreans, 24 Americans) were selected from the universities in Seoul, Korea and Minnesota, the United States. All participants were in their 20s without intellectual, auditory, visual or speech-language disorders. Students were divided into two groups (a Korean group and an American group). There were 24 students in each group. In the Korean group all participants’ native language was Korean, and in the American group all participants’ native language was English. Table 1 summarizes the participants’ information.

Experimental Materials

Target social words

Based on core vocabulary in Korean as well as in other languages found in the previous studies (e.g., Banajee et al., 2003; Boenisch & Soto, 2015; Kim et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2009; Lee et al., 2011; Robillard et al., 2014; Trembath et al., 2007), social words with high frequency of use were selected. Among these social words, 10 social words including ‘Hi (안녕)’, ‘That's good (그래)’, ‘Yes (응)’, ‘No (아니)’, ‘Thank you (고마워)’, ‘I’ m sorry (미안해)’, ‘I like it (좋아)’, ‘I don’ t like it (싫어)’, ‘I’ m fine (괜찮아)’, ‘I don’ t know (몰라)’ were selected as final stimuli (Figure 1). To demonstrate the validity of selected social words in Korea and the United States, 6 specialists in the department of communication disorders, 3 experts from Korea and 3 experts from the United States, conducted social word validity checklist with 5-point scale. The collected scores from validity checklist were averaged in Appendix 1 and used to counter-balance the frequency of use.

Display

Graphic symbols representing each of the 10 social words were selected from PCS (Mayer-Johnson) which is widely used in American culture, and Ewha-AAC symbol (Park et al., 2014) which is developed appropriately for Korean culture. The symbols were retrieved by search for symbol labels that represented the 10 social words. Each of 20 graphic symbols, 10 graphic symbols selected from PCS and the other 10 graphic symbols selected from Ewha-AAC symbol, was assigned to a slide of PowerPoint presentation, and presented on the screen via a projector.

Experimental Procedures

Two types of tasks were conducted in a classroom. Twenty sheets of PowerPoint slides with 20 graphic symbols of 10 social words were presented for the participants in random order on the screen via the projector.

Transparency task

Before one of the slides of 20 graphic symbols on a screen was shown to the participants, the researcher put a questionnaire for transparency task in front of the participants on the desk. After the researcher provided instructions for the transparency task (e.g., ‘Please write your own thoughts about pictures as follows.’), the participants were asked to guess and write down meanings of the presented graphic symbols in 30 seconds for each slide.

Translucency task

After the transparency task, the researcher gave instructions the translucency task (e.g., ‘The researcher will tell you the meaning of each picture. After you listen to it, please mark how you agree with the meaning of the picture on the rating scale.’). As participants watched the 20 sheets of slides which were identically shown in the task 1, the researcher provided each social word of each symbol, and gave 20 seconds for each slide. In the previous pilot study, 30 seconds were given for each slide. However, 10 seconds were short-ened because 30 seconds for each slide were deemed excessive for the translucency task. The participants who were presented with the social word and graphic symbol and were asked to rate their match on a 5-point scale.

Data Analysis

For the transparency task, 1 point was assigned to an answer of a participant corresponding with the original social word, and 0 points to each incorrect answer. Although the majority of the participants wrote plural responses, only the first response of each graphic symbol was the target answer to be scored. The scores of the translucency task were counted differently. Rating scores of the 5-point scale were substituted for points of each item.

Statistical Processing

A 2×2 two-way mixed ANOVA, with groups (Korean, American) as the between subject factor and with types of symbol (PCS, Ewha-AAC symbol) as the within subject factor was conducted. In order to identify whether there were differences on the transparency task performance and the translucency task performance between two groups according to graphic symbol types.

The Spearman rank correlation coefficients were calculated to identify any associations of the transparency task performance between two groups, and the translucency task performance between two groups in the aspects of each social word AAC symbol. Additionally, the Spearman rank correlation coefficients were calculated to identify any relationships between the transparency task performance and the translucency task performance of each group and among the total participants in the aspects of each social word AAC symbol.

Reliability

To demonstrate the reliability of scoring for the transparency task, the researcher and a graduate student in the Department of Communication Disorders participated in scoring and checked the reliability. The total amount of the collected answers for the transparency task was scored and compared between two scorers. The reliability score between the two observers was 97.5% for the transparency task of the Korean group, and 93% for the transparency task of the American group.

RESULTS

Comparison of Transparency Task Performance

Comparison transparency task performance of two groups according to symbol types

The study intended to establish statistically significant differences on the transparency task performance of the Korean group and the American group according to the two types of symbol sets. In PCS, the American students performed better than the Korean students, but in Ewha-AAC symbols, the Korean students performed better than the American students. In order to identify whether these variations were significantly different or not, a 2×2 two-way mixed ANOVA was conducted. The results from the 2×2 two-way mixed ANOVA show that a main effect for the groups was not statistically significant (F(1,46) = 1.282, p = .263). Meanwhile, a main effect for the symbol types was statistically significant (F(1,46) = 10.209, p < .005). That is, the mean score of Ewha-AAC symbol (= 4.792) is significantly higher than the mean score of PCS (=3.938). Also, a two-way interaction between groups and symbol types was statistically significant (F(1,46) = 15.797, p < .0001). The significant two-way interaction was caused by contradictory results of the task performance between the Korean group and the American group in each symbol type. The Korean group showed lower performance than the American group in PCS, but in Ewha-AAC symbol they showed higher performance than the American group.

Comparison transparency task performance of two groups according to each social word AAC symbol types

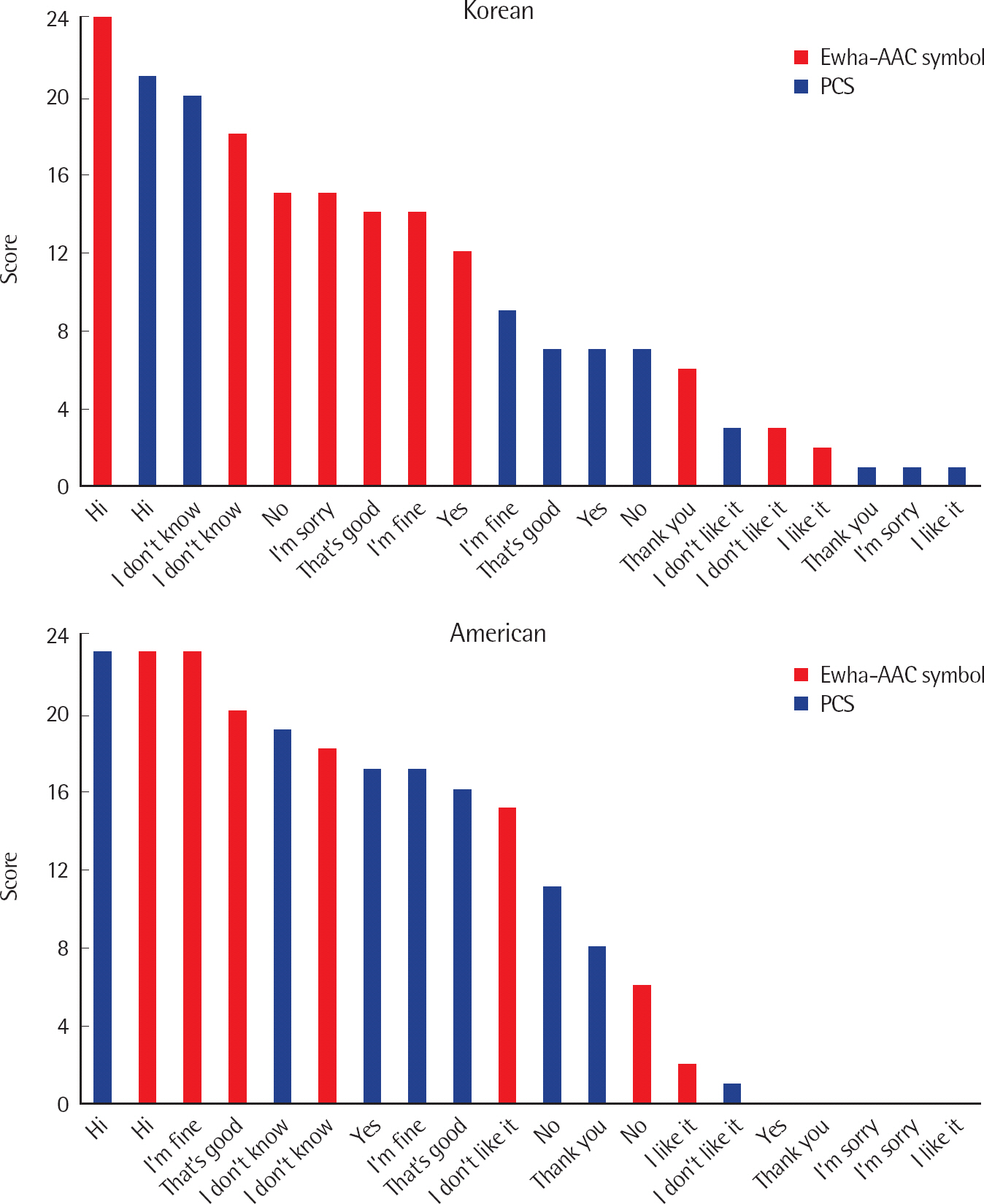

The Spearman rank correlation coefficient was calculated in order to identify any association between the results of the transparency task performance between the Korean group and the American group according to each social word AAC symbol. The Spearman correlation coefficient in the rank of social word AAC symbols from the transparency task performance between the Korean group and the American group was .628 (p < .005) which implies they are moderately and positively correlated. The symbol with the largest rank gap was ‘I’ m sorry’ (Ewha-AAC symbol), and the symbol with the smallest rank gap was ‘Hi’ (Ewha-AAC symbol). In case of ‘I’ m sorry’ (Ewha-AAC symbol), 15 Korean students gave the correct answers, but all of the American students gave incorrect answers. Meanwhile, ‘Hi’ (Ewha-AAC symbol) showed the smallest rank difference and the largest number of correct answers in both cultural groups. Additionally, ‘Hi’ (PCS) and ‘I don’ t know’ in both symbol types also showed small rank gap and large number of correct answers, too. However, ‘I’ m sorry’ (PCS) and ‘I like it’ (PCS) with small rank difference showed the smallest number of correct answers in both cultural groups. On the contrary, large rank differences of ‘Yes’ (Ewha-AAC symbol) and ‘No’ (Ewha-AAC symbol) were caused by larger number of correct answers from the Korean students than the American students. Detailed information about the order of social word AAC symbols by score form the transparency performance between the Korean students and the American students is presented in Figure 2 and Appendix 2.

Comparison of Translucency Task Performance

Comparison translucency task performance of two groups according to symbol types

The study intended to establish statistically significant differences on the translucency task performance of the Korean group and the American group according to the two types of symbol sets. In PCS, the American students rated higher scores than the Korean students, but in Ewha-AAC symbol, the Korean students rated higher scores than the American students. In order to identify whether these variations were significantly different or not, a 2×2 two-way mixed ANOVA was conducted. The results from the 2×2 two-way mixed ANOVA show that a main effect for the groups was not statistically significant (F(1,46) = .05, p = .823). Also, a main effect for symbol types was not statistically significant (F(1,46) = .291, p = .592). Meanwhile, a two-way interaction between groups and symbol types was statistically significant (F(1,46) = 75.160, p < .0001). The significant two-way interaction was caused by opposite task performance of the Korean and American in each symbol type. The Korean students gave lower points than the American students in PCS, but in Ewha-AAC symbol they rated higher scores than the American students.

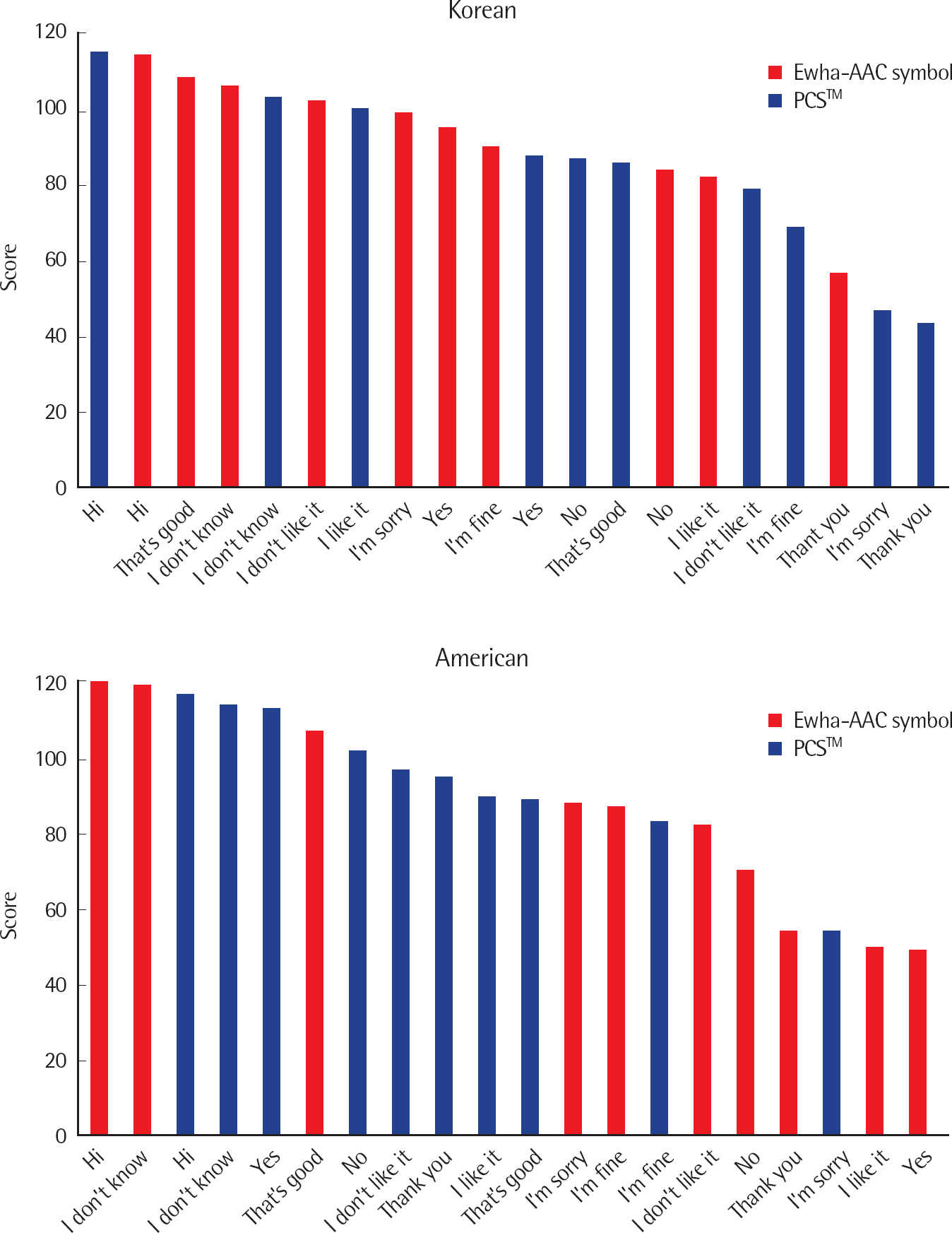

Comparison translucency task performance of two groups according to each social word AAC symbol

In order to identify any association between the results of the translucency task performance of the Korean group and the American group according to each social word AAC symbol, the Spearman rank correlation coefficient was calculated. The Spearman correlation coefficient in the rank of social word AAC symbols from the translucency task performance between the Korean group and the American group was .596 (p < .01) which implies they are moderately and positively correlated. The symbol with the largest rank gap was ‘Thank you’ (PCS), and the symbol with the smallest rank gap was ‘Thank you’ (Ewha-AAC symbol). In case of ‘Thank you’ (PCS), the American students gave 95 points, but the Korean students gave 43 points for it. Meanwhile, ‘Thank you’ (Ewha-AAC symbol) showed the smallest rank difference since the two cultural groups gave similar points to it, 56 from the Korean group and 54 from the American group. Additionally, ‘Hi’ and ‘I don’ t know’ in both symbol types also showed small rank gap and high scores from each cultural group. However, ‘I’ m sorry’ (PCS) with small rank difference showed low scores in both cultural groups. On the contrary, large rank difference of ‘Yes’ (Ewha-AAC symbol) was caused by higher scores from the Korean students than the American students. Moreover, ‘I don’ t like it’ in both symbol types showed large rank gap because of opposite scoring between the two groups. Detailed information about the order of social word AAC symbols by score form the translucency performance between the Korean students and the American students is presented in Figure 3 and Appendix 3.

Correlations between Performance of Transparency Task and Translucency Task

Task and Translucency Task In order to identify any associations between the results of the transparency task and translucency task for 20 social word AAC symbols which were used in this study, the Spearman rank correlation coefficients were calculated.

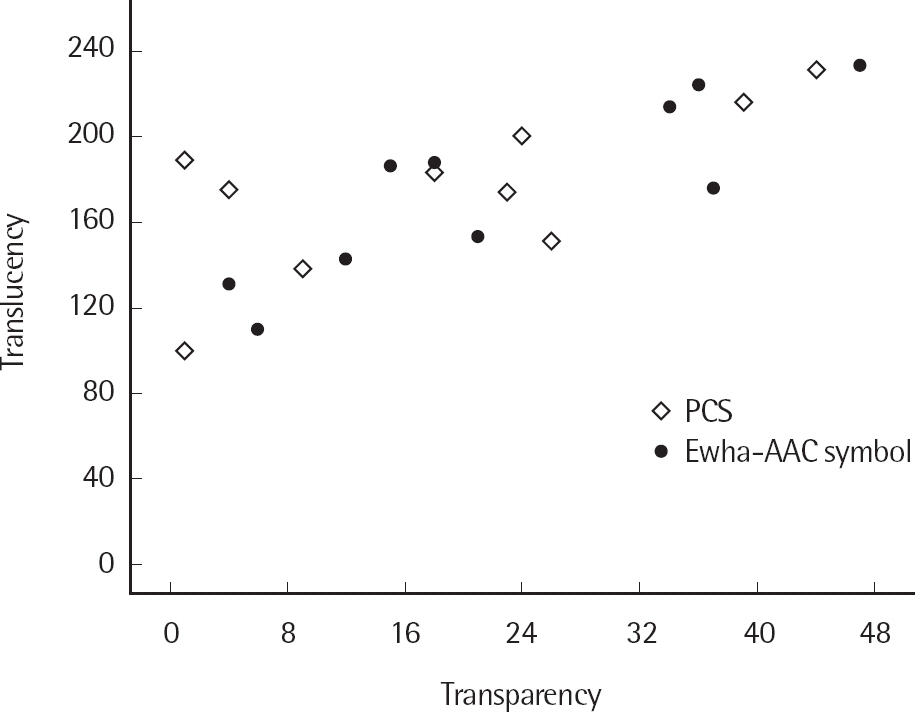

The Spearman correlation coefficient in the rank of social word AAC symbols between the transparency task performance and translucency task performance of the Korean group was .685 (p < .001) which implies they are moderately and positively correlated. Additionally, the Spearman correlation coefficient in the rank of 20 social word AAC symbols between the transparency task performance and translucency task performance of the American group was .670 (p < .001) which implies they are moderately and positively correlated. Furthermore, the Spearman correlation coefficient in the rank of 20 social word AAC symbols between the transparency task performance and translucency task performance among the total participants was .707 (p < .0001) which implies they are moderately and positively correlated. Figure 4 shows the Spearman correlation in the rank of 20 social words AAC symbols which were used in this study.

The Spearman correlation in the rank of social word AAC symbols between the transparency task performance and translucency task performance of total participants. The maximum score of each social word AAC symbol is 48 for the transparency task and 240 for the translucency task.

AAC=augmentative and alternative communication; PCS=Picture Communication Symbols.

CONCLUSION

Transparency Task Performance of Two Cultural Groups

This study showed that the two cultural groups, the Korean and American undergraduate students, guessed the meaning of social word AAC symbols differently according to symbol set types, PCS and Ewha-AAC symbol. There were no significant differences between the two groups on their performance of transparency task according to symbol types. However, there were significant differences between the two symbol set types. That is, social word AAC symbols in Ewha-AAC symbol were more guessable symbols than those in PCS for the participants of this study.

In the aspects of each social word AAC symbol, there was moderate and positive correlation in the rank of social word AAC symbols from the transparency task performance between the Korean and American group. Top three ranked social word AAC symbols were similar for both groups: ‘Hi’ (Ewha-AAC symbol), ‘Hi’ (PCS), and ‘I don’ t know’ (PCS) for the Korean students, and ‘I’ m fine’ (Ewha-AAC symbol), ‘Hi’ (Ewha-AAC symbol), and ‘Hi’ (PCS) for the American students. Meanwhile, bottom ranked social word AAC symbols were interestingly different between the two groups, for the Korean students ‘Thank you’, ‘I’ m sorry’, and ‘I like it’ in PCS were bottom ranked symbols and all of them scored 1 point. In the case of the American students, however, ‘Thank you’, ‘I’ m sorry’, and ‘Yes’ in Ewha-AAC symbol and ‘I’ m sorry’ and ‘I like it’ in PCS were bottom ranked symbols since all of them scored 0 point. For the Korean students, PCS, which were developed in American culture, were difficult to guess, and for American students Ewha-AAC symbols, which were developed in Korean culture, were also hard to guess. This result was consistent with the previous findings that cultural background affects symbol recognition (Chompoobutr et al., 2013; DeKlerk et al., 2014; Nigam, 2003).

In the aspects of social words as referents, ‘Hi’ and ‘I don’ t know’ in both symbol types showed high percentage of correct answers in both cultural groups, in case of ‘Hi’ in PCS, the rank gap between the two groups was the smallest. Meanwhile, ‘Thank you’ and ‘I’ m sorry’ were bottom ranked social words in the two groups. The rank gap of ‘I’ m sorry’ in Ewha-AAC symbol and ‘Thank you’ in PCS between the two groups were large, but ‘I’ m sorry’ in PCS showed small rank gap. Although social words have low concreteness as referents for AAC symbols, social word ‘Hi’ and ‘I don’ t know'seemed to have higher concreteness regardless of cultural background. In this study, both cultural groups answered correctly for AAC symbol ‘Hi’ and ‘I don’ t know’ in different symbol types which described ‘Hi’ with a person waving hand and ‘I don’ t know’ with a person shrugging their shoulders. On the contrary, the low percentage of correct answers and large rank rap of ‘Thank you’ in PCS may be caused by using American Sign Language for representing its meaning which Koreans are not familiar with. Additionally, ‘I’ m sorry’ in Ewha-AAC symbol showed the largest rank gap between the two groups because more than half of the Korean students answered correctly, but all of the American students answered incorrectly. ‘I’ m sorry’ in Ewha-AAC symbol described a down-headed boy with folded hands which is common action to express remorse in Korean culture, but not common in American culture. This result can support the previous study that showed referent is an influencing factor for symbol recognition (Schlosser & Sigafoos, 2002; Yovetich & Young, 1988), and implied that a symbol also contains a referent's cultural characteristics if a referent itself has cultural backgrounds.

Translucency Task Performance of Two Cultural Groups

In this study, the two cultural groups, the Korean and American undergraduate students, differently scored the degree of translucency on social word AAC symbols according to symbol set types, PCS and Ewha-AAC symbols. There were no significant differences between the two groups on their performance of translucency task according to symbol types. Additionally, there were no significant differences between the two symbol set types in the translucency task. That is, social word AAC symbols in PCS and Ewha-AAC symbol received similar scores on the 5-point rating scales assessing the degree of translucency on social word AAC symbols.

In the aspects of each social word AAC symbols, there was moderate and positive correlation in the rank of social word AAC symbols from the translucency task performance between the Korean and American group. The top three ranked social word AAC symbols were similar on both groups: ‘Hi’ (PCS), ‘Hi’ (Ewha-AAC symbol), and ‘That's good’ (Ewha-AAC symbol) for the Korean students, and ‘Hi’ (Ewha-AAC symbol), ‘I don’ t know’ (Ewha-AAC symbol), and ‘Hi’ (PCS) for the American students. Meanwhile, the bottom ranked social word AAC symbols were interestingly different between the two groups. For the Korean students ‘Thank you’ and ‘I’ m sorry’ in PCS were bottom ranked symbols. For the American students, however, ‘Yes’ and ‘I like it’ in Ewha-AAC symbol were bottom ranked symbols. For the Korean students, it seemed difficult to agree that PCS symbols perfectly expressed referents’ meanings, and the American students could not easily agree with symbols from the Ewha-AAC symbol set and their meanings as well. This result can support the previous study that showed individuals with different cultural backgrounds do not recognize graphic symbols similarly on the translucency ratings (Blake Huer, 2000).

In the aspects of relationship between social words and AAC symbols, ‘Hi’ in both symbol types were top scored social word in the two cultural groups, and in case of ‘Hi’ in Ewha-AAC symbol, the rank gap between the two groups was small. This result implies that both cultural groups agree with the social word ‘Hi’ and graphic symbol depicting a hand-waving person. Additionally, ‘I don’ t know’ in both symbol types also showed small rank difference and high score. This result also implies that the participants of this study strongly agree with the graphic symbol with a shrugging person and social word ‘I don’ t know’. However, the rank gap of ‘Thank you’ in Ewha-AAC symbol was the smallest, but it gained low scores on the rating scale. This result implies that although the rank gap of ‘Thank you’ in Ewha-AAC symbol between the two groups was the smallest, both groups disagreed with the description of the social word ‘Thank you’ which described two persons: one was giving a ball and the other was bowing toward the giver. Meanwhile, ‘Thank you’ in PCS showed the largest rank gap between the two groups. The Korean students scored the lowest points on it, because the graphic symbol expressed ‘Thank you’ with American Sign Language. Additionally, ‘Yes’ in Ewha-AAC symbol showed the secondly largest rank gap between the two groups, because the American students gave the lowest points to it. In case of the social word ‘Yes’, PCS described a nodding-face, but Ewha-AAC symbol described a big red circle. For the American students, it seemed hard to agree with social word ‘Yes’ and a big red circle. ‘I don’ t like it’ in both symbol types showed big rank difference between the two groups. Although the social word was identical, the description of each graphic symbol in each symbol type was different. To represent ‘I don’ t like it’, a person holding a sign ‘X’ in Ewha-AAC symbol and an annoying face sticking out its tongue in PCS. Interestingly, the Korean students scored high points on ‘I don’ t like it’ in Ewha-AAC symbol, the American students, however, scored high points on the symbol in PCS. The results from this study imply that the similarities and differences in symbol description may affect the translucency of symbols.

Relationship between Performance of Transparency Task and Translucency Task

Task and Translucency Task In this study, there were moderate and positive correlations in the rank of social word AAC symbols between transparency task performance and the translucency task performance in each cultural group and among the total participants.

Such correlations do not explain the causal relationship between transparency and translucency as influencing factors of symbol recognition. However, these results may support the study of Huang & Chen (2011) which found a positive association between transparency and translucency in graphic symbols and suggested that symbols with high transparency and translucency affect the initial symbol learning. In this regard, the positive correlations between the performances of the two types of iconicity tasks suggest that transparency and translucency of graphic symbols may affect the symbol recognition. Moreover, the results suggest to consider the degree of transparency and translucency of graphic symbols when selecting symbols for AAC.

Limitations of this research are as follows. Diversity of participants was quite limited. This study involved twenty-four adults for each cultural group. All participants in both groups were female, in their early 20s, and undergraduate students. Follow-up study is required to secure sufficient diversity of participants for each group because it would be difficult to generalize the results of the current study with the limited characteristics of participants.