과제특정적 혀 근긴장이상증으로 인한 마비말장애

Task Specific Lingual Dystonia: An Uncommon Cause of Isolated Dysarthria

Article information

Abstract

Objectives:

Dysarthria is a common neurologic symptom and is produced by a variety of neurologic disorders. Hyperkinetic type of dysarthria is indicated as a plural disorder because it includes many heterogeneous involuntary movements including dystonia. Isolated dysarthria due to lingual dystonia is rarely encountered. We describe a patient presenting with isolated dysarthria caused by lingual dystonia.

Case:

A 50-year-old man visited our hospital due to dysarthria. His medical and psychological history was not remarkable. The results of neurological examinations did not reveal any motor or sensory abnormalities. However, on speech examination, he demonstrated dystonic movements of the tongue aggravated on speaking and during rest with mouth opening. The dystonic movements disappeared when he protruded his tongue and did not occur during chewing or eating behaviors. After exclusion of other causes of tongue dystonia, he was diagnosed as having primary lingual dystonia.

Conclusion:

We presented a patient with isolated dysarthria caused by dystonia specifically involving the tongue. Our case illustrates that task specific lingual dystonia should be considered as one of the causes of isolated speech disturbances.

Dysarthria is a motor speech disorders that is caused by various neurological diseases including peripheral neuropathy, neuromuscular junction disorders, and pyramidal and extrapyramidal central nervous system lesions. It can be classified into different types of dysarthria depending on the characteristics of neurologic and speech disturbance, such as flaccid, spastic, ataxic, hypokinetic, hyperkinetic, unilateral upper motor neuron, and mixed type (Duffy, 2005).

Hyperkinetic dysarthrias are often associated with diseases of the basal ganglia control circuit and concurrently show involuntary movements that interfere with normal speech productions. This type of dysarthria is indicated as a plural disorder because it includes many heterogeneous involuntary movements (Duffy, 2005). Huntington disease is a degenerative disorder which is most commonly associated with hyperkinetic dysarthrias. However,other involuntary movements such as myoclonus, dystonia, spasm, and tremor also can affect speech production and demonstrate different characteristics of speech disturbances depending on involved movements.

Dystonia is slow and sustained involuntary movements characterized by abnormal postures. However, dystonia may involve only oral/facial muscles and cause specific speech disturbances. Lingual dystonia is commonly presented as a form of neuroleptic-induced tardive dystonia (Tan & Jankovic, 2000). In addition, it is occasionally reported in patients with brainstem (Lee & Yeo, 2005) or thalamic infarction (Kim et al., 2009), or as a post-traumatic movement disorder (Ondo, 1997). However, isolated primary lingual dystonia has rarely been described. So far, limited numbers of cases with primary focal lingual dystonia have been reported (Baik, Park, & Kim, 2004; Degirmenci, Ors, Yilmaz, & Karaman, 2011;Ishii, Takaoka, & Shoji, 2001; Ozen, Gunal, Turkmen, Agan, & Elmaci, 2011; Papapetropoulos & Singer, 2006; Tan & Chan, 2005). Herein, we describe a patient with dysarthria caused by lingual dystonia. Interestingly, the dystonic movements were aggravated on speaking and preferentially appeared during rest with mouth opening but subsided with protrusion of the tongue.

CASE REPORT

A 50year-old man was admitted to our hospital due to a subacute onset of dysarthria that had developed two weeks earlier. He complained that his tongue was curled during speaking, but he had no discomfort while chewing or swallowing. His medical history was unremarkable, and he denied of using any antidopaminergic drugs, including gastrointestinal prokinetics and neuroleptics.

Neurological examination showed that there was no definitive weakness in the tongue, masseter, and facial muscles. Tough, pinprick, cold temperatures and vibration sensations were normally perceived in the face and tongue. On speech examination, he showed inconsistent articulatory breakdowns throughout the speech with alternative (/tΛ/, /kΛ/) and sequential (/pΛtΛkΛ/) motions of the tongue. However, articulatory abnormalities were not observed on producing bilabial sounds, such as /pΛ/. On his conversational speech and reading, irregular changes of stress and rates of speech were also observed. The symptoms were aggravated by keeping him speaking.

Further examinations of oral motor functions revealed intermittent contractions of his tongue muscles occasionally inducing involuntary movements during mouth openings. These movements were involuntary and could not be controlled by his will. The involuntary tongue contractions did not bother him from chewing or eating, and were not observed while he swallowed test materials, which was confirmed by video fluoroscopy. However, the abnormal tongue movements disappeared while he protruded his tongue. There were no involuntary movements in other body parts, including his jaw and mouth. Electromyographic study in the bilateral genioglossus muscles did not show any abnormal discharges on rest.

Other neurological examinations showed normal results, as were the results of routine hematologic, biochemical, and thyroidfunction tests and tests for Wilson disease. Brain magnetic resonance imaging showed no abnormal findings. After exclusion of secondary causes of tongue dystonia, he was diagnosed as having primary lingual dystonia. Initial treatment with 1.5 mg of clonazepam for one month failed to improve his symptoms, but a change to 6 mg of trihexyphenidyl resulted in moderate improvements. Two months after starting trihexyphenidyl treatment, his involuntary tongue movements were no longer observed while resting. However, mild dysarthria was occasionally presented during connected speech.

DISCUSSION

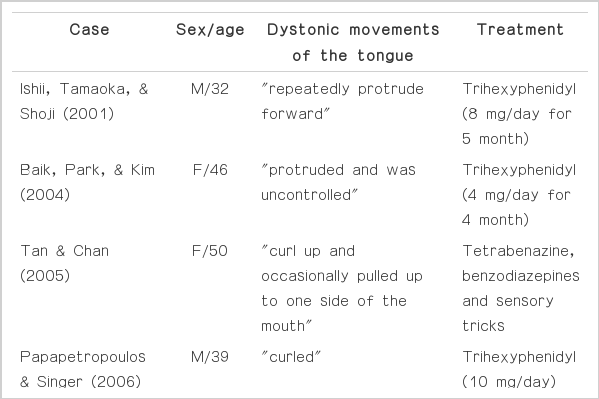

The patient presented with isolated dysarthria that was caused by dystonia specifically involving the tongue. Although the most common form of lingual dystonia is the A 50year-old tardive dystonia (Tan & Jankovic, 2000), it can be found in patients with cerebral infarction (Kim et al., 2009; Lee & Yeo, 2005) or recognized as a post-traumatic movement disorder (Ondo, 1997). Patients with isolated primary lingual dystonia are rare. (Baik et al., 2004; Degirmenci et al., 2011; Ishii, Takaoka, & Shoji, 2001; Ozen et. al, 2011; Papapetropoulos & Singer, 2006; Tan & Chan, 2005). The dystonic contractions of the tongue were protrusions with or without lateral displacement and it was always induced by speaking (Table 1). In contrast to npost-traumatic tardive dyskinesia, these patients are relatively young, and do not show involuntary movements in other facial muscles such as the jaw, mouth and eyes. Moreover, their symptoms were generally responsive to anticholinergic medications as in our patient even though recent study reported that botulinum toxin injections could be an effective way to release such symptoms.

Interestingly, our patient’s lingual dystonia that was aggravated during mouth opening was subsided when he protruded his tongue. This observation appears to be contrary to dystonic movements of the tongue described in previous reports, which included protrusional tongue movements (Table 1). Thus, idiopathic tongue dystonia may not be a homogenous disorder. During tongue protrusion, the activation of genioglossus muscle plays a central role (Papapetropoulos & Singer, 2006) while the activity of extrinsic muscles is relatively reduced in resting position. The activity of extrinsic muscles of the tongue is relatively reduced in resting position or during speech. According to animal studies (Altschuler, Bao, & Miselis, 1994; Dobbins & Feldman, 1995; Guo, Goldberg, & McClung, 1996; McClung & Goldberg, 1999; Pittman & Bailey, 2009; Sokoloff, & Deacon, 1992), tongue protrusion is controlled by the motor neurons in the ventral part of the nucleus, whereas retrusion is regulated by those in the lateral and dorsolateral part. The remainder of the nucleus controls intrinsic muscles of the tongue. Previous studies reported that central pattern generators of one movement suppressed those of the other during respiration and swallowing (McFarland & Lund, 1995; Sawczuk & Mosier, 2001), similar processes may functionally operate in intrinsic or extrinsic muscles of the tongue. Therefore, it may be assumed that lingual dystonia of our patient mainly involves the intrinsic muscles of the tongue and subsides during the interaction of the extrinsic muscles.

In addition, our patient’s lingual dystonia was induced or aggravated by speaking but not by chewing or swallowing. Indeed, we observed that involuntary tongue contractions aggravated on reading while they disappeared during oral-pharyngeal phases of swallowing on videofluoroscopy. The pattern generator in the brainstem for the tongue movement is controlled by the cortical projection. According to an intracortical microstimulation experiment using monkeys, the firing rates of electrodes recording neuronal activities in the tongue-representing cortical area are differentially modulated depending on the tasks of tongue protrusion or swallowing (Martin, Murray, Kemppainen, Masuda, & Sessle, 1997). Thus, the cortical patterns of controlling oral motor activities may also be different between speech and nonspeech tongue activities (Bunton, 2008). Our patient showed clinical evidence of posture/task specific lingual dystonia and provides further evidence supporting for these experimental data.

In summary, our patient showed that primary lingual dystoniaaggravated by speaking should be considered as one of the causes of isolated speech disturbances. Suspecting this diagnosis would be of practical importance because anticholinergics may be efficacious in these patients.

Notes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (No. 2010-0024353).